Canada's Famed and Beautiful Forests Aflame

|

| The Donnie Creek wildfire in northeastern B.C. Photo by B.C. Wildfire Service |

"[Typically, fires larger than 1,000 hectares in Canada last around three weeks on average, while fires larger than 10,000 hectares can burn for approximately 40 days on average.""Some active fires have been burning for several weeks already."Mohammad Reza Alizadeh, post-doctoral associate MIT, researcher, bioresource engineering, McGill University"[This] could be happening probably for the rest of our lives or until the forest burns out, and it will be seasonal. We are going to see more fires every summer.""Now it's pushing all the way through October into November and even in Alberta, which is a really cold place, they've had wildfires in the middle of the winter because it's been so dry and there's been so little snow.""You could have a hot muffler on an ATV or a car or a Jeep. You could have a careless person with fireworks. You could have a campfire that wasn't put out properly or that threw some sparks.""The conditions in 2015 that precipitated the Fort McMurray fire were nearly identical to the conditions we're seeing all across Northern Canada right now, which are record-breaking high temperatures in the 30-degrees-Celsius range and rock-bottom relative humidity. The forest fuels -- the leaves, the sticks, the soil, the grass -- are very, very dry and so they catch on fire, not like a wet leaf or a piece of moss, but like a piece of newspaper."John Vaillant, author, Fire Weather: The Making of a Beast (2016 Fort McMurray wildfires)

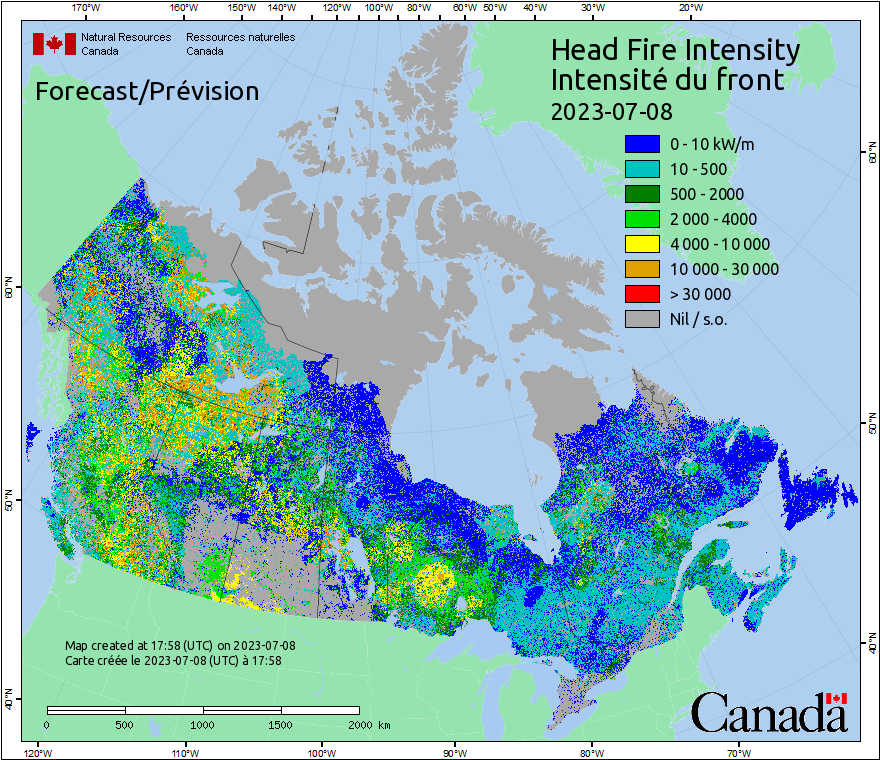

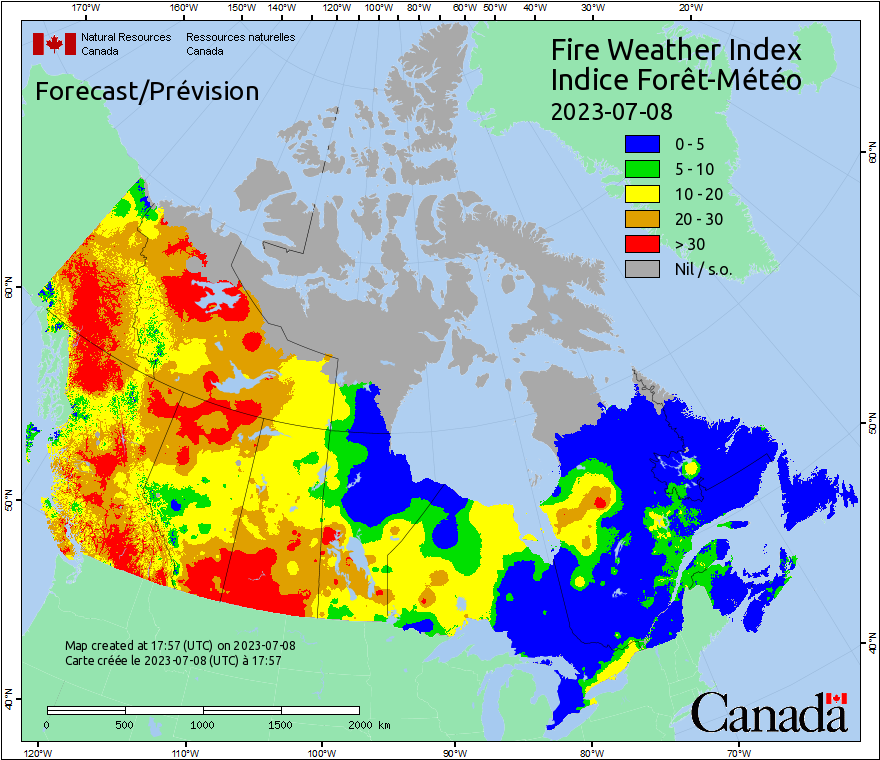

From coast to coast this lamentably unusual year, intense wildfires spread throughout the breadth and depth of the second largest national geographical land mass on Earth. "The risk of forest fires is going to remain very high", director general Michael Norton with the Canadian Forestry Service stated recently. From British Columbia in the West to the Atlantic provinces in the East of the country, Natural Resources Canada speaks of unprecedented wildfires.

Wildfires in Canada's world-precious forests that act as a global carbon sink, have produced huge plumes of smoke, wind-driven far and wide. The intense fires have produced intense acridity affecting air quality from drifting particulate matter in province after province, with shifting winds taking them far abroad to the United States and even to Europe. Total area burned by wildfires in one season by June 27 surpassed the historical record.

The 2023 wildfire season is far from over, with 8.8 million hectares so far having been burned as opposed to the previous record of 7.6 million hectares through the entire 1989 season. By July 5 there were 3,412 fires so far this season; while the 10-year average stood at 2,751 fires per season. In 2023, 639 of those fires remain active, 351 of that total in the "out of control" category.

The evacuation rate has been equally remarkable, with an estimated 155,856 people having been forced from their homes across 132 evacuation orders throughout the country. Historically, Canada's wildfire season runs from April through September, with most activity taking place in July and August. This year's intense fire season began in May and could remain at an intense level until season's end. El Nino's expected onset could make wildfire conditions even worse.

|

| A recruit works to contain and put out a fire near Merritt, B.C., during a training exercise. Though hard hats and other gear are standard for wildfire fighters, respiratory protection is not. (Ben Nelms/CBC) |

For the maintenance of ecosystems, wildfires are considered to be a natural phenomenon essential to remove dead vegetation. Some fires are started by humans, but lightning remains the most common wildfire trigger. Close to three in four fires were confirmed this season to have been started by lightning, but hot weather conditions make forests more flammable, making it likelier a fire could result from human activity.

"You're often in smoke. Even on a small initial attack, you're usually breathing smoke.""When you're 22 and doing it, you don't think about it. But once you get over 30 and you start feeling the burn, it creeps up on you. That I might have to think about this down the road.""Waking up with a kind of smoke hangover in the morning. When that smoke settles, you're breathing it in all night and you'll wake up with that wheeze and that headache.""You're in the forest. You're taking branches to the face. You're wet. You're sweaty. You're hot. And you're out there doing 16-hour days and then you wear something when you're sleeping in your tent at night? Probably not. It's just I don't know if they can really design something for wildland fire."Ian Sachs, 13-year veteran firefighter, British Columbia

"Unfortunately, there isn't a great standard presently for firefighters that have to work in dynamic fire situations, in wildland and wildland urban interface settings in other places across the globe.""There's no real mandatory requirements for proper respiratory protection that filters out carbon monoxide, volatile organic compounds, and these fine particulates that we know are associated to the diseases that are killing firefighters.""We unfortunately bury too many firefighters because of the diseases they acquire from exposures on the fire ground. We can't put the genie back in the bottle when those exposures happen."Neil McMillan, director of science and research, Occupational Health, Safety and Medicine Division, IAFF (International Association of Fire Fighters)

In certain areas, high temperatures produce lightning-initiated wildfires because the environment becomes more dry, prompting lightning to trigger and spread fires. Heat causes evaporation from trees foliage and grass, making them increasingly flammable. John Vaillant, an expert on wildfires, points out that 21st century fires are characterized by abnormally hot and fast flames that firefighters find it exceedingly difficult to combat.

"Over the past seven years, everybody who has been in one of these new severe 21st century fires -- firefighters and civilians alike -- have just been astonished by how fast the flames move across the landscape."

|

| Firefighters with the B.C. Wildfire Service put out hot spots on the McKay Creek wildfire north of Lillooet in 2021. (B.C. Wildfire Service) |

Government agencies have mobilized 3,790 provincial firefighters along with Canadian Armed Forces personnel helping with airlifts and firefighting action. Equipment is mobilized between provinces by the Canadian Interagency Forest Fire Centre, supporting air evacuations, while evacuees have been hosted by municipalities.

International support has aided Canada in dealing with the wildfires in recognition that this wildfire season has stretched and challenged Canada's firefighting capacity. The number of international firefighters has totalled 3,258 that Canada has called upon, coming from six continents and eleven countries to give assistance over the season's course. 1,754 international firefighters are currently helping in the fight against wildfires in Canada.

There are signed agreements between Canada for firefighting assistance from Australia, Costa Rica, Mexico, New Zealand, South Africa, the United States and Portugal. And they have all responded to Canada's appeal for international help.

"Even without the fire, the smoke is already extraordinarily dangerous for their health [older adults, children with asthma, those with breathing and heart conditions]. And you can't even see.""These fires, the way the smoke billows out of these fires, it turns day into night. You need your headlights on in the middle of the day and you can't even see anyway because the smoke is so thick."John Vaillant, author of Fire Weather: The Making of a Beast

Labels: Canada's 2023 Wildfire Season, Catastrophic Level of Wildfires, Evacuations, Forestry Losses

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home