What It’s Like to Live in an 84-Square-Foot House

What It’s Like to Live in an 84-Square-Foot House

Courtesy of Dee Williams

Dee Williams is an Olympia, Washington-based teacher, designer, woodworker, and sustainability advocate who owns Portland Alternative Dwellings, where she designs and builds tiny houses. Here at the Eye, Williams shares an excerpt adapted from The Big Tiny, her new memoir published by Blue Rider Press.

The book details her reflections on living in a portable 84-square-foot

house parked in a friend’s back yard that she built herself after a

health crisis–inspired epiphany compelled her to simplify her life.

Now that I had my trailer on order, I needed to fully flesh out the

design. I took the plans and manipulated them, switching the location of

the kitchen and bathroom, the sleeping loft and living room;

envisioning what it would feel like to wake up in a space the size of my

backcountry tent, and which direction I would face while sitting on the

toilet. I wanted to design the house around my body and my needs,

instead of following the pattern that I’d fallen into in my big house:

picking paint colors and finishing the woodwork with some future owner

and salability in mind. This was going to be my house.

I started examining the way I draped clothes over the chair in my

bedroom as I undressed at night, and how I automatically reached for the

light switch just below shoulder height on the right, no matter what

room or building I entered. I noticed how much space I needed to chop an

onion or make a peanut butter sandwich, the height of my existing

kitchen counters, the cabinets, and chairs. I measured the height of the

toilet, the depth of my closet, and the amount of room my torso

consumed when I sat up in bed—all so I could design a house that fit my

body and my needs, instead of someone else’s. I felt like Jane Goodall,

observing my behavior and wondering at the mystery of why I always

brushed my teeth starting with my right bottom molars, why I always

double-checked that the coffeepot was unplugged before I left for work

in the morning, and why I always leaned forward with my left ear cocked

when trying to define the odd sounds that I heard outside the window

late at night.

Courtesy of Dee Williams

The more I took note of how my body and brain clicked along through

the day, the more I realized that I spent a considerable amount of time

banging around with a brain full of chatter; a rush of things to do,

bills to pay, telephone calls, text messages, emails, worrying about my

job or my looks, my boobs or my ass; I rushed from thing to thing,

multitasking, triple-timing, hoping to cover all the bases, avoiding

anything that might disrupt the schedule or routine. At times, I was so

caught up in the tempo and pattern, the predictable tap tap tap of each

day, that there was no time to notice the neighbors had moved out, the

wind was sneaking in from the north, the sun was shifting on its axis,

and tonight the moon would look like the inside of an enormous cereal

bowl. I wondered when I had become a person who noticed so little. I had

no idea that the distance from the floor to the top of my knee was 24

inches, which seemed to explain why I was always popping it on my car

bumper.

Things had changed for me after I landed in the hospital. I truly

seemed to be seeing the world in a new way, but I still needed to

challenge myself to try to tune in, to notice the connections between

what things were (the toilet paper holder, light switch, doorknob) and

how they connected to me, so suddenly I understood how the height of the

bathtub made it easy to get in and out of the shower, and the way the

handle of the front door was low enough to grasp even when my arms were

full of groceries.

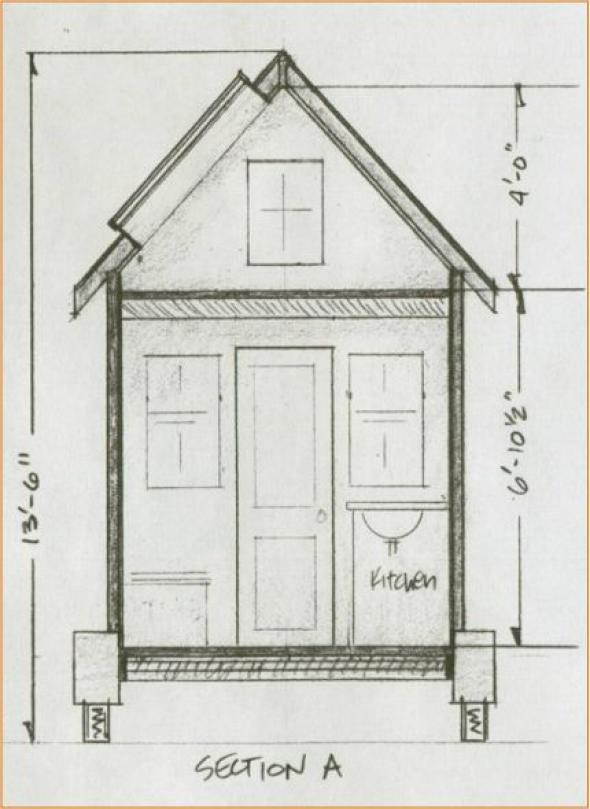

The overall size of my house could be no taller than 13½ feet from

the pavement to the peak, and no wider than the wheel wells of the

trailer (8½ feet). That meant I spent days and hours trying to sort

through the pros and cons of a lower ceiling in the kitchen to

accommodate a taller ceiling in the loft, and figure out how could I

cram everything I loved into a house the size of an area rug.

Courtesy of Dee Williams

The bathroom and kitchen seemed to absorb the greatest amount of

time, leaving me wringing my hands while I considered all the things I

wanted (a small oven, three burners, pantry, refrigerator, freezer, food

prep area, cupboards for dishes, drawers for tea towels, silverware,

pots, pans, toaster, a shower, toilet, bathroom sink, and a place to

store all my grooming tools and “boo-boo dust,” as my sister and I

called our lotions and potions). But there was only so much space. I

made of a list of pros and cons, and argued with myself, trying to

imagine what the future me might want and what she would say about the

old me’s choices.

Ultimately, because of the tight quarters, I settled on imagining

what would be necessary if I was staying in a remote cabin, and

developed a sort of glorified list of necessities.

I landed on a decision to install a small one-burner stove called the

Princess. It was a marine stove suitable for the types of meals I

regularly cooked: small, elegant, and poised for something more ... just

like a princess. I had to be brutally honest with myself, I rarely used

my existing four-burner stove and oven, an appliance that was labeled

“Magic Chef,” a mismatch for my particular flair, which was opening up

soup cans and pouring the contents into a waiting pot. The Princess left

room for the ceramic sink that I’d found in the crawl space of my big

house, a beautiful hand-thrown bowl fitted with a tiny pipe that instead

of draining to the city sewer would dribble into a giant Ball jar to be

dumped in the garden. At the local RV store, I tried on the various

bathroom setups, units that allowed you to sit on the toilet while

taking a shower, or to crouch in a baby bathtub with your knees near

your ears while you sipped wine and enjoyed a nice tub soak. These units

were almost exclusively made out of fiberglass cloth impregnated with

styrene (a possibly carcinogenic chemical that smells to high heaven).

An outdoor shower and compost toilet seemed like my only option.

Courtesy of Dee Williams

I agonized over which should take up more space inside my postage

stamp of a house: a refrigerator large enough to hold a week’s worth of

food, beer, and half-and-half, or a composting toilet that according to

the pamphlet was too big to fit in the trunk of my car? I chose neither.

I shrank the refrigerator down to the size of an undercounter icebox,

and decided to venture forward with a bucket composter—a system that

required me to manage the waste along with my organic kitchen scraps in a

compost barrel outside the house (a decision I made only after reading a

hefty book called The Humanure Handbook, a

really great manual that walked through the various diseases, germs,

bugs, and social phobias we all carry when it comes to our poop).

The only major unknown was the shower. There wasn’t any room for it

inside the house; there wasn’t an easy way to heat up the water, deliver

it to a showerhead, and dispose of it safely. I was stuck, and after

staying up till three in the morning one night, thumbing through the

Lehman’s catalog, a book that included photos of all the ways the Amish

and off-grid settlers bathe, I decided to buy a membership to a gym. I

figured I could get a membership at one of those big national gyms, so

wherever I went from town to town, I could shower as much as I wanted.

Courtesy of Betty Udesen

All of this consternation—trying to sort through how much I could

bend without breaking when it came to modern conveniences—left me one

part freaked out about living in the little house, and one part

over-the-top excited.

It also begged me to ask a thousand times a day: What am I doing?

What is the point? And every time, something deep inside me would shoosh

me and say: “Because you can! That’s the point of all of this. You can

do this! You can build a simple, kind house ... nothing fancy, no big

deal ... just a little house that will fit you more or less.”

After a month or so of playing around with layouts, after examining

all my little quirks and patterns, I came up with a floor plan for the

little house. I invited friends to dinner, greeted them at the door,

masking tape in hand, and showed them the blueprint I’d taped out on the

living room rug. “This will be the kitchen,” I offered. “And this will

be the bathroom,” I explained, shifting my weight to the right. “The

sleeping loft will be above, and here,” I said taking two steps

forward, “is the great room.” I stood on the leeward end of rug and

threw my hands over my head like pom-poms.

Courtesy of Dee Williams

They stared at me with a mixture of concern and curiosity.

"Umm,” one friend asked, “doesn’t that make the great room [she said

it with little finger quotes] the size of the dining room table?” She

wanted to know if I was joking.

It wasn’t a joke, but I had to admit I was curious about whether or

not it could be done. I felt that it could in the same way I was certain

it would fun to try climbing Mount Adams, Mount St. Helens, and Mount

Hood all in a single weekend. Of course it was possible!

As we ate dinner sitting on the living room rug, my friends joked

about how I could vacuum the tiny house with a tiny Dustbuster and could

pull it through a car wash when the windows needed cleaning. After a

few beers, we played a game like Twister, tumbling over each other while

standing on the rug, seeing if we could reach for a pillow off the

imaginary living room couch while sitting on the toilet, or open the

front door and reach for a coffee cup on the far side of the kitchen

without ever stepping foot in the house. Before everyone left that

night, I gave each of them something pulled randomly from the kitchen: a

bottle opener, a wineglass, a ladle, or a set of pot holders that

looked like chicken heads.

The downsizing had begun.

Adapted and reprinted with permission from Blue Rider Press, copyright 2014.

Labels: Architecture, Social-Cultural Deviations

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home