Roadside Testing for Marijuana Impairment

"There is no legislation right now where a number means anything. It means nothing in the law. Until we get a number [in judging the amount of THC in a driver's urine or bloodstream], we will have no number to prosecute."

"We're having our challenges. The most pressing one is that we don't know what the legislation will look like. It makes it hard to train and prepare."

"Young people between 15 and 24 don't think cannabis use has any effect on driving, and that police can't do anything about it."

"We have to create a culture that doesn't accept the use of cannabis and the operation of a motor vehicle."

Superintendent Gord Jones, Toronto Police, co-chair, Canadian Chiefs of Police, traffic committee

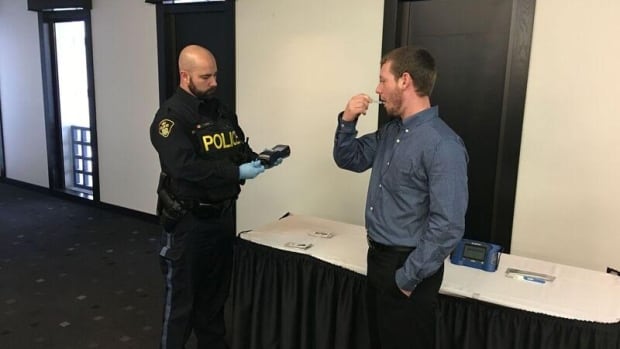

An Ontario Provincial Police officer demonstrates the use

of a roadside drug-screening device. The Toronto Police, along with the

OPP, are taking part in a pilot project testing two such devices.

(Ontario Provincial Police)

Drivers who become suspects of drug use, under legislation brought into law in 2008 are required to take part in drug evaluation under the auspices of a Drug Recognition Expert (DRE), officials drawn from among police forces who have undergone training along international standards and who also rely on the experience of observations when determining whether a blood or urine test is warranted in specific situations.

At the present time across Canada fewer than 600 trained DRE officials can be deployed, while a 2009 assessment estimated that to be effective, Canada would require between 1,800 and 2,000 such officers on active duty. Currently, the training system preparing DRE officers hasn't been given the mandate nor the equipment to prepare such trained officers any speedier than they do now. In other words, at a time when the number of marijuana-infused drivers is on the cusp of increasing with soon-to-be legalized marijuana in the country, there is a lag in preparedness on that front.

And this, when it is well known that Cannabis use has a detrimental affect on reaction time, visual function, concentration and short-term memory. Symptoms relating to the use of cannabis include poor concentration, uneven balance, the reduced capacity to divide attention, along with elevated pulse and blood pressure, visibly dilated pupils, red eyes and eyelids, or body tremors, all visible to the trained eye.

What is as yet unclear is how much the chemical responsible for the psychological effects in marijuana, -- THC -- it would take to produce an impaired driver, according to the

Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse. Such effects are idiosyncratic to the individual, where the person who may be impaired substantially after ingesting a modest amount of marijuana reacts differently than another person who may present as merely moderately impaired using a similar dose of marijuana to the first.

In 2015, Statistics Canada reported some 75,000 impaired driving infractions, 2,500 of which were related to drugs. Studies find that a sizeable proportion of drivers, on the other hand, who die in motor vehicle accidents have drugs in their systems reflecting the use of all manner of drugs, exclusive of alcohol. A third of fatally injured drivers, aged 15 to 24 were also found to have used a variety of drugs, according to a 2010 study.

"We're getting a picture that people who are using cannabis are dying in greater numbers than ever before", advised Douglas Beirness, senior researcher with the Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse.

It's a complex issue. Police can readily detect the signals that an alcohol-impaired driver conveys; the odour of booze, for example, on the breath. There may not be an odour associated with cannabis to link it with a user, however, since users increasingly consume it in edible products. If there is an odour of pot, or a positive test following a fatal accident, the cannabis might have been used at a much earlier date, since the chemical traces of cannabis linger in the body.

"Drugs affect everyone differently based on the drug and the way the body metabolizes the drug", explained RCMP Sgt. Ray Moos, national co-ordinator of the DRE program. Training in the DRE program is conducted in a two-stage model, starting with a ten-day classroom session whee trainees are familiarized in recognition of the way drugs, licit and illicit, impair the user's body. They must pay attention to symptoms of blood pressure and heart rate abnormalities and to this end DRE officers carry a kit with a stethoscope, blood pressure cuff and thermometer.

The classroom portion of the training is followed by a four-day field certification process where subjects are analyzed for recognizable impairment. The DRE is called to respond when police stop a suspect driver. The individual may then face a demand by the DRE officer to provide a urine, saliva or blood test at a police station, representing a half-hour process. The resulting tests are forwarded to a toxicology lab, of which the RCMP have three, the OPP and QPP having their own labs.

Some of the equipment that Toronto

police will use in a pilot project testing roadside drug-screening

devices. (Supplied)

Labels: Canada, Driving Under the Influence, Marijuana

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home