Nature's Teflon

"It's almost oily feeling, like a lubricant. It is actually these things that are happening on the scale of single mineral grains that control how much energy is released. We think it's the very fine clay found in the northern Pacific that was causing this specific kind of fault structure and that led to the runaway slip in the Tohoku-Oki earthquake."One of 27 scientists representing ten countries on a 50-day expedition named the Japan Trench Fast Drilling Project, aboard the Chikya, an international drill ship, Dr. Rowe was describing the fine clay that was found, packed between two gigantic tectonic plates under the ocean floor; the Pacific plate slipping into the Eurasian plate just east of Japan. And it was this slippage that took place in 2011 that shocked Japan and the world with the destructive Tohoku-Oki earthquake and tsunami.

"To our knowledge, it's the thinnest plate boundary on Earth."

Dr. Christie Rowe, geologist, McGill University, Montreal

|

| LATimes.com |

The crew, attempting to find some geological-scientific answers to the intensity of that monstrous earthquake and the immense tsunami it spawned, which in turn destroyed a series of nuclear installations at one of Japan's nuclear power plants, triggering a triple catastrophe, had to contend with a grudging environment, with their vessel rocked by huge swells.

Each time bad weather intruded on their experiment they were forced to retrieve equipment enabling them to drill at incredible depths: "Having that pipe hanging under the boat can be quite dangerous in a storm if it starts swinging", explained Dr. Rowe. She was speaking of drilling equipment and the need to haul up kilometres of equipment each time swells exceeded six metres.

Eventually they succeeded. Hitting bottom to examine where and why the Earth experienced a massive rupture on March 11, 2011 east of Sendai, Japan that hit an unbelievable 9.1 on the Richter scale. The expedition managed to get their drilling equipment through 6,900 metres of water to drill over 800 metres into the seabed, and finally installing probes and temperature sensors in the fault zone.

The scientists aboard the vessel have the task of studying the ancient clay "down to the nanoscale", said Dr. Rowe, to attempt to understand how that friable clay acted as an enabler allowing the giant plates to slip under and over one another. The area is called a subduction zone, describing the tectonic plates' potential to slide past one another; frictional heat measured by the temperature sensors in the boreholes allowed the plates to leap 50 metres in the space of three minutes.

|

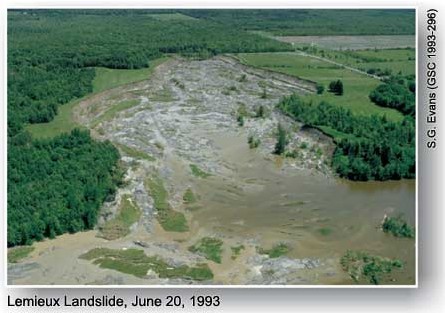

File photo of Lemieux landslide, June 22, 1993. Aerial view of slide. John Major/Ottawa Citizen |

The landscape of eastern Canada has been left with a similar clay deposit, called Leda clay, comprised of tiny particles, residue from the bottom of an ocean; in the case of eastern Canada, the ancient, former Champlain Sea. A portion of the village of Note-Dame-de-la-Salette in Quebec slid into the Lievre River in the middle of the night in 1908, and 34 people died.

In June of 1993, a hillside collapsed, sending millions of tonnes of earth and forest into the South Nation River nearby the town of Lemieu. A sudden collapse, no warning whatever. "I looked over, and I could see the forest moving", said a cabinet-maker, driving his Ford Ranger into what had been Country Road 16, and suddenly was a vast open space. "I thought to myself, 'What's wrong with this picture?"

His reaction was not instinctively swift enough to prevent his truck from a ten-metre drop. In the Saguenay Valley village of Saint-Jean-Vianney, the village dropped in seconds in 1971 about 30 metres creating a landslide that killed 31 people. Sodden after a wet autumn following a wet spring after a winter of several thaws, the Leda clay that appears solid when dry, was saturated to the extent its clay particles would no longer stick together.

"These are probably even slipperier clays (than around Ottawa), if you can believe it", said Dr. Rowe. "They are very weak at low slip rates. But they are even weaker at high slip rates, and once you start sliding in a landslide or an earthquake, this would encourage it to run away. It's the closest thing we have in the world to a natural Teflon."

"It takes a while for the water to permeate through the clays. It's not directly predictable by what the weather conditions are."

Labels: Canada, Geology, Japan, Natural Disasters, Nature, Science

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home