New Hope Potential Out of Personal Tragedy

"With the opioid crisis and persistent high rates of intravenous drug use, we have a great number of potential lung donors who are hepatitis C-positive, many of whom didn't even know they were sick when they were alive."

"The current protocol is to not use these organs [from deceased hepatitis C donors] but we started to question if that still made sense in an era when direct antiviral agents can cure hepatitis C."

"So I think it's a big gain and patients will get transplanted sooner as well, as more organs become available for transplantation."

Dr. Marcelo Cypel, thoracic surgeon, Toronto General Hospital

|

| Donor lungs from individuals infected with hepatitis C have been successfully transplanted into 10 patients at Toronto General Hospital (TG), University Health Network (UHN) |

Harvesting organs from the deceased to enable those with failing organs to receive an award of another chance at prolonging their lives, has a kind of ghoulish atmosphere about it, but the recipients are universally grateful that this opportunity to live longer with the removal of their failing, diseased organs and the replacement of healthy alternatives giving them that proverbial 'new lease' on life. hepatitis C affects an estimated 250,000 Canadians.

Moreover roughly 40 to 70 percent of people living with hepatitis C remain unaware that the blood-borne virus enjoys harbour in their bodies. The disease, when it is identified, has a 98 percent cure rate for those infected, with the use of antiviral drugs. So it makes perfectly good sense to use organs of those who are infected. Those transplant organs solve the problem of failing organs, even given the fact that they carry the blood-borne disease, since post-surgery with a treatment protocol of antiviral drugs hepatitis C is eliminated.

The treatment following organ transplantation serves as an effective preventive of the organ recipient becoming infected with the virus that has the potential to destroy their liver. Surgeons at Toronto General Hospital have committed to performing transplants of lungs from deceased donors with hepatitis C for eleven patients, representing a pilot study, to evaluate the safety of these infected organs transplanted to prolong life.

The very idea of using hepatitis C-infected organs for transplantation was unthinkable previously, before the introduction of antiviral drugs with the capacity to cure the disease. Now that drug overdoses with the advent of opioid substitutes like fentanyl and carfentanil has caused an explosion of inadvertent deaths, some good is seen to come from a dismal situation of expanding numbers of drug-user deaths.

|

| Dr. Marcelo Cypel estimates there could be 1,000 more lungs available for transplant every year in North America by using hepatitis C positive organs (Photo: UHN) |

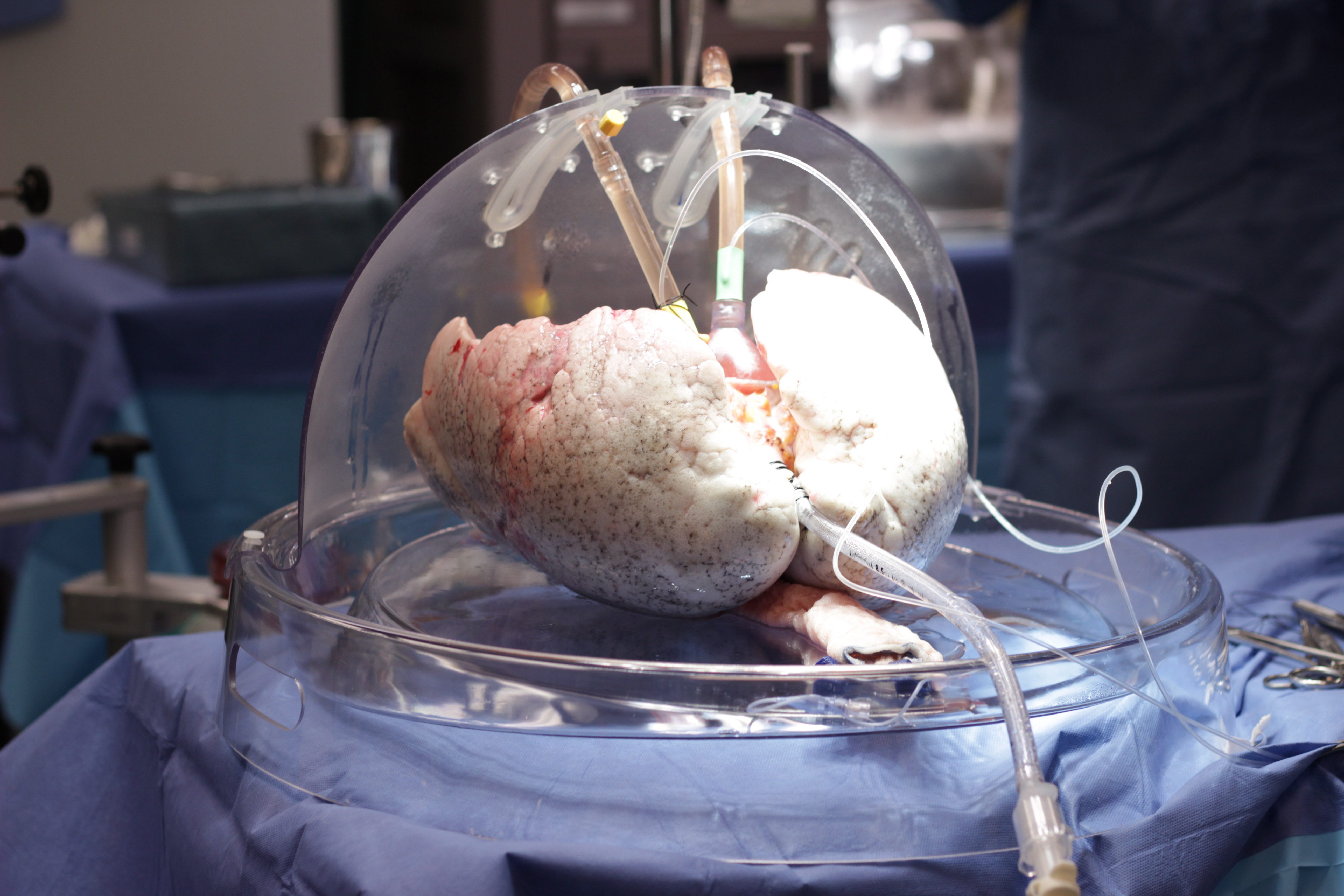

Researchers from the hospital located in Toronto initiated their study last fall; their goal, to enrol twenty patients whose desperate need of a lung transplant would drive them to agree to what might seem risky to some; receiving an organ known to be hepatitis-C-positive. The compelling argument -- that a device known as the ex-vivo lung perfusion (EVLP system) developed as it happened, at that same hospital in 2008, will ensure that the blood-borne virus would be cured -- is persuasive.

A special solution baths the donor lungs for a six-hour period after which doctors evaluate their condition and asses suitability for transplant purposes. The perfusion technique has the effect of removing about 85 percent of residual blood in the lungs. Once the transplant has taken place, a follow-up within two to four weeks tests recipients for the presence of hepatitis C, and a 12-week therapeutic course of antiviral drugs takes place in prevention of liver infection.

|

| Developed at UHN, the Toronto Ex Vivo Lung Perfusion System (EVLP) perfuses organs outside of the body. (Photo: UHN) |

Should the virus take up residence in the liver, it can often take decades before it manifests itself through inflammation the virus causes which can then lead to severe cirrhosis or liver cancer. Eight transplant patients have thus far completed treatment for hepatitis C, and given a virus-free diagnosis. Two of the patients remain on the drugs, while one awaits the medication protocol to begin, post-surgery.

As far as Dr. Cypel is concerned, this new protocol will result in "a huge boost in organ donations", with a potential for adding approximately one thousand more donors annually in North America, which sees about two thousand lung transplants performed each year. There were over 240 patients awaiting lung transplant in 2015 in Canada; one in five died while on the waiting list, as a result of insufficient organs available for transplant.

"Obviously, when you first think about infecting someone, it raises some concerns."

"But we also recognized that these people are on a transplant list waiting for a life-saving organ, and without a transplant or even a delay in their transplant, it can sometimes be too long a wait and there can be grave consequence if they have to turn down these organs."

"I hope that if we can show that this is a very safe and effective strategy, which I think our results already show, then I think this can be expanded to other organs. So we could likely expand this from lungs to kidneys and heart, as well as pancreas and small bowel transplants."

"And it’s important because sometimes one single donor can be a donor of multiple different organs."

Dr. Jordan Feld, TGH liver specialist, study co-author

|

| Lungs are seen in a device known as an ex-vivo lung perfusion or EVLP in this undated handout photo. Toronto doctors have successfully transplanted lungs from deceased donors with hepatitis C into patients in need of the life-saving organs, followed by treatment to prevent them from becoming infected with the potentially liver-destroying virus. THE CANADIAN PRESS/HO/ University Health Network |

Labels: Bioscience, Organ Transplants, Research, Toronto General Hospital

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home