A Deadlier Ebola

"It's very difficult to prove that a mutation like this is responsible for the severity of the epidemic ... But it would have to be a pretty amazing coincidence."

"We think that the mutation is actually an adaptation to humans [excluding adaptation to infect the assumed reservoir animal harbouring Ebola, bats]. It's kind of a signal to us that this mutation was selected for replication of the virus in people, which I would argue is further evidence that this mutation is significant and is not just a coincidence."

Jeremy Luban, virologist, University of Massachusetts Medical School

"As virologists we weren't really convinced [that the virus hadn't adapted. We thought ... some of these changes might be affecting the biology of how the virus behaves."

"Once it's in humans, that's the new host. It's really got to acquire adaptations and get the most fit for in human-to-human transmission."

"We feel that the two papers together make a really powerful case."

"We know that these viruses are causing human infection, we know that they're evolving, but do we really know what that evolution means?"

Jonathan Ball, professor, University of Nottingham, England

|

| A burial team at work during the West African Ebola crisis in Liberia in 2014. Researchers now believe that a genetic mutation may have made one strain of the virus more suited to entering human cells. (DANIEL BEREHULAK / The New York Times) |

Drs. Jeremy Luban and Jonathan Ball each led a team of investigators and independently of one another produced a study that turned out to reach like conclusions. As it turned out the two teams of virologists had their studies published in the journal Cell. Their studies identified a mutation that altered Ebola haemorrhagic fever virus; at least that part of it that infiltrates receptors on the outside of the host cell; that host cell that is in humans, to make it more infectious and more lethal.

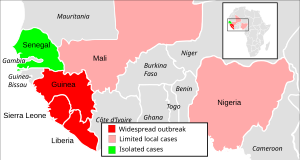

The West African outbreak that concerned scientists and medical professionals and governments between 2013 and 2016 menaced vulnerable people in rural and urban areas of West African, killing over 11,300 people before it was wrestled to a standstill through the international community of medical professionals and research scientists focusing on the outbreak declared by the World Health Organization to have become a pandemic, a public health emergency. Although it struck hardest in Africa it also appeared in Britain and Sardinia, and secondary infections occurred worryingly in the United States and Spain.

The research conducted by Dr. Luban led him to the conclusion that the mutant versions were "better at fitting into the lock [receptors on the host cell] and got into the cell better". Having infiltrated the cell the virus succeeded in reproducing itself to get on with its deadly work, the purpose of its existence. It took mere months for this mutated strain to dominate the epidemic where some 90 percent of those who became affected did so through the mutant version of the virus.

Beginning in Guinea in late 2013, it remained unknown why a hundred times greater numbers of people became infected in comparison to any other previous outbreak of the virus. It was estimated that in the course of 28,000 infections the virus mutated enabling it to infect more people, a function of reproduction. Natural selection served to aid the mutation to spread its deadly effects. What threw scientific study off was the hardest hit areas also had the worst public health infrastructure.

The researchers reconstructed the evolution of the Ebola virus, identifying where the pathogen began its genetic alterations. One mutation, a single nucleotide change on a gene whose purpose was to build the glycoprotein "key", appeared to have been persistent, and it was this altered gene that their attention focused on. The research team led by Dr. Ball attached the mutant glycoprotein to another virus entirely to test its capacity to infiltrate host cells.

The finding was that the mutant was infinitely more efficient entering human cells and those of other primates in comparison to the standard version. But the vector that harbours Ebola in between human outbreaks appeared not to have been infected by the mutant; its specialty remained the invasion of human cells. Coincidentally, Dr. Luban whose normal field of study is HIV infection, was in the process of an unrelated experiment on a number of viruses which happened to include Ebola when he noted one variant of Ebola appeared proficient at infecting cells.

Dr. Ball, liaising with epidemiologists, identified the variant as a mutant that appeared early in the outbreak, and then spread throughout the affected region. The realization struck both researchers only after their teams wrote up their findings for publication, that they had identified the same mutation, which they named glycoprotein mutant A82V. The mutant, it is felt, likely wiped itself out finalizing the outbreak.

Meant specifically to infect human cells, it was not recognized as a threat able to retreat into the reservoir population of bats to be resurrected at some later time.

Labels: Africa, Bioscience, Ebola, Nature, Research, Science, virus, WHO

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home