Outwitting a Virus

|

"The disease we know as the flu is caused by the influenza virus, which mostly lives in fowl and pigs; humans catch it through close contact with those animals."

"The 1918 outbreak was caused by an H1N1 variant that was first noticed in an army camp in the United States."

"It's hard today to describe the speed of the virus's spread and the scale of its staggering devastation."

Mike Callaghan, medical anthropologist, Switzerland

|

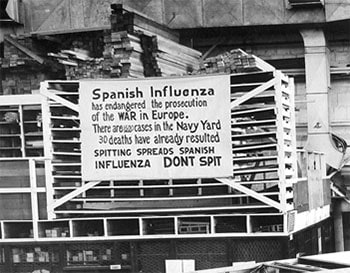

| The 1918 flu pandemic is sometimes called “The Spanish Flu” not because it originated in Spain, but because that nation had remained neutral during the war and freely reported news of flu activity. |

"The 1918 flu pandemic occurred during World War I; close quarters and massive troop movements helped fuel the spread of disease."

"In the United States, unusual flu activity was first detected in military camps and some cities during the spring of 1918. For the U.S. and other countries involved in the war, communications about the severity and spread of disease was kept quiet as officials were concerned about keeping up public morale, and not giving away information about illness among soldiers during wartime. These spring outbreaks are now considered a “first wave” of the pandemic; illness was limited and much milder than would be observed during the two waves that followed."

"In September 1918, the second wave of pandemic flu emerged at Camp Devens, a U.S. Army training camp just outside of Boston, and at a naval facility in Boston. This wave was brutal and peaked in the U.S. from September through November. More than 100,000 Americans died during October alone. The third and final wave began in early 1919 and ran through spring, causing yet more illness and death. While serious, this wave was not as lethal as the second wave. The flu pandemic in the U.S. finally subsided in the summer of 1919, leaving decimated families and communities to pick up the pieces. Scientists now know this pandemic was caused by an H1N1 virus, which continued to circulate as a seasonal virus worldwide for the next 38 years."

What was familiarly called the "Spanish flu" was a pandemic; it broke out all over the world. A world at war. Where, it was explained, an aggregation of people in close quarters helped its swift spread. Great swaths of military personnel were moved around from country to country, helping the virus which turned deadly, to spread with swift ease. At one time, it would be mostly country people, people who lived and worked on farms and had close contact with animals and birds who were at risk and the spread of the virus was limited because they remained where they were, locally.

At the very time that the world is remembering the two great world wars that brought death and destruction to the global community, the hundred-year anniversary of the start of the First World War, considered in its wholesale death toll, to be 'the war to end all wars' is being recognized. In lock-step with that global conflict was the global affliction of the "Spanish flu". Spain, as a neutral country at the time of World War I, had no restrictions imposed on news of the influenza epidemic it was suffering, unlike those countries at conflict who kept the news from their public already struggling with the demoralizing stories out of war zones.

That strain of influenza destroyed more lives than both world wars' totals of military and civilian deaths as consequences of the two global conflicts. In the first six months of the flu's onslaught close to 50 million people died worldwide. By the time it was over, when no further waves of infection occurred, an estimated 100 million people were dead as a result of the flu. It was not the flu we face yearly with its recognized symptoms that puts people low for several days to weeks. This was a pathological scourge that killed.

When one in three people world-wide became infected and died, combating armies became short of fighting men. Half their soldiers were bedridden. Civilians were instructed to wear face masks at all times. Eventually the lethal strain wore itself out by 1920. Since then medical science has been anticipating another massive viral flu outbreak with dread. But the combination of contagious impact and lethality has not yet been replicated. And the yearly recommendations that populations be inoculated against the flu has its genesis in hopes of averting a worst possible scenario.

People with compromised immune systems, people with chronic illness and disease, the elderly and the very young depend on the herd immunity concept; the greater the numbers of people for whom the onset of illness through the impact of protective inoculation the less likely the possibility of a widespread breakout in a largely unprotected population. In 1918's globalized flu pandemic populations with no immunity were suddenly exposed to the virus. Because of the war populations migrated, both military and civilian.

At that time long-distance travel was accomplished through rail and ship primarily. In our modern era with rapid transit where airline passenger jets can traverse the globe in hours, not weeks, where products are shipped globally and with them germs are transmitted with incredible speed. That speed accomplishes an amazing feat of transmission by a virus that reacts swiftly to impediments. Each year a combination of the commonest flu strains prevalent in China the year before is produced in the hope that the following year's strain would be closely aligned for successful immunity.

The flu virus is a swiftly mutating trickster, shifting in response to the presence of any remedy produced to impact its deadly efficacy. By the time a vaccine is produced the virus has undergone change and becomes more effective in its deadly delivery. Because it is so capable of mutating to meet the challenges meant to destroy its efficacy, it is always one step ahead of remedies to modify its effectiveness and potentially bring its impact to a halt, boosting the body's immune system to deflect its ingress.

It has proven itself adept at developing new strategies to resist medication, to survive in new environments and to negate its transmission. It is a formidable foe for medical science, a medical community anticipating that a day will arrive when it will once again forcefully impact on a global scale with deadly precision. There is no global conflict ongoing at the present time, other than an increasingly chilly 'cold war', to enhance and invite a viral outbreak in response to a dense gathering of warring factions worldwide.

But there are other types of wars, in a world where trade and economics and mercantile interests come into play. Such as sanctions as punishment by one entity against another in a conflict of a different kind. The current trade war between the United States and China has been a complicating factor in stalling the ongoing trade between China's production capabilities and its far reach throughout the world where its products are always in demand. Among other items that are in demand is China's cooperation in providing intelligence on flu strains.

China's ownership of this intellectual property has enabled it to turn its sole-source data into a critical bargaining chip, one that leaves vaccine researchers struggling to come up with a combination that will present as a deterrent to this year's flu strain -- without the vital data it depends upon from China.

Researchers in pathogen transmission know that should a deadly new strain of flu arrive it would impact their capacity to mobilize resources quickly and effectively to combat airborne, contagious, fast-acting viruses.

To succeed, however, there must be a scaffolding comprised of cooperation, restraint and above all unprecedented levels of research focusing on a virus whose reactive abilities and mobility are frighteningly legendary.

|

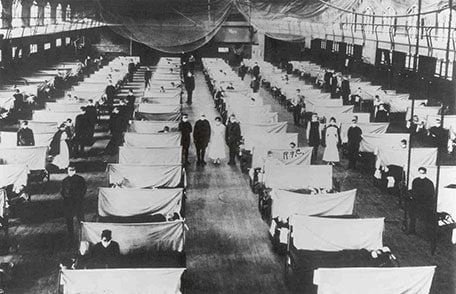

| Ready and willing, these volunteers were on the forefront of the 1918 pandemic response. Today, influenza viruses continue to pose one of the world’s greatest health challenges. |

Labels: Centenary, Health, Immunization, Influenza, Research, Vaccines, virus

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home