Curing The Ills Of The World

"The scratching hurt my eyes so much I could barely go out in the sun to plow. I was always rubbing them."

"My vision is much better now. I can recognize people. I can work."

Shiva Lal Rana, farmer, Geta, Nepal

"The pain is excruciating. People tell me it's like sandpaper scratching over your eye every time you blink [Eventually, the cornea is scarred, slowly decreasing vision until blindness sets in].""Once you get to a particular stage, it's irreversible."

"Ghana has eliminated a painful eye disease which has devastated the lives of millions of its most vulnerable people for years. But the fight does not end here. Many other countries are on the cusp of elimination and must continue to push for the elimination of trachoma -- and other neglected tropical diseases -- across the world."

"The disease thrives in areas that are traditionally short of water."

Simon Bush, director, tropical diseases program, NGO Sightsavers

|

| Fuseini Kwadja, an ophthalmic nurse, screens communities in Yendi, Ghana. |

China, Gambia, Iran, Iraq and Myanmar claim to have been successful, as a result of a global campaign to wipe out the incidence of trachoma among their populations -- a common affliction of vulnerable people living in Third World conditions lacking proper hygiene and basic amenities that would ensure bacteria resulting from inadequate-to-no latrines are available to isolate human feces from contaminating food and water are kept to a minimum.

Worldwide, according to the World Health Organization's statistics, an estimated 1.2-million people have no vision whatever because of living conditions leading to infections causing trachoma, The WHO further estimates that 190 million people living in infection-vulnerable countries, some 41 in total, are at risk. More people are blinded by cataracts, but they do not result from infections.

While the scientific world community has been focused on fighting the horribly debilitating and often deadly effects of AIDS, malaria and Ebola, for several decade the medical community worldwide has also been focusing on trachoma. According to experts, enforcing basic public health practices is hugely effective in solving much of the problem of infections leading to trachoma.

Millions of people have lost partial eyesight from the effects of trachoma. And roughly seven million sufferers have undergone a brief intervention to reverse the effects of inward-torqued eyelids resulting from trachoma. In addition, 21 million trachoma sufferers suffer from infected lids that can be cured without resorting to surgery. The inversion of inward-torqued eyelids is a surgical procedure, one that takes only 20 minutes to complete.

Mr. Rana, a 65-year-old farmer in Nepal, arrived at the Geta Eye Hospital, a 32 kilometer trip he undertook by walking there, with the request that doctors pluck out his eyelashes. The bacterial infection had swollen and inverted his eyelids so that he suffered excruciating discomfort every time he blinked and his lashes raked his corneas. What he really feared was that the scratches they left and the resulting scar tissue would ultimate blind him.

Doctors responded to his plight by performing a new type of operation. His eyelids were sliced open, then rolled back and sutured, with the lashes facing outward once again. He was prescribed and given antibiotics to clear up the infection. That was fifteen years ago. Nepal's success in eliminating the outcome of this endemic infection led the WHO to declare Nepal's success in clearing up a critical public health condition; the sixth such country to manage that milestone.

Twenty years ago the global campaign to eliminate trachoma was launched, and it has been so successful that Cambodia, Laos, Mexico, Morocco and Oman have succeeded in eliminating the public health problem resulting from the infection. Now, Nepal and Ghana have joined them. The WHO still awaits requests from China, Gambia, Iran, Iraq and Myanmar to achieve certification attesting to their self-proclaimed success.

When fewer than five percent of a country's children show symptoms of trachoma and fewer than one in one thousand adults have vision loss from scarred eyeballs this is taken to represent elimination having succeeded. New cases of trachoma emerge in Nepal yearly, resulting from Nepalis working as seasonal labourers in India. Chlamydia trachomatis, the bacterium, is transmittable from person to person.

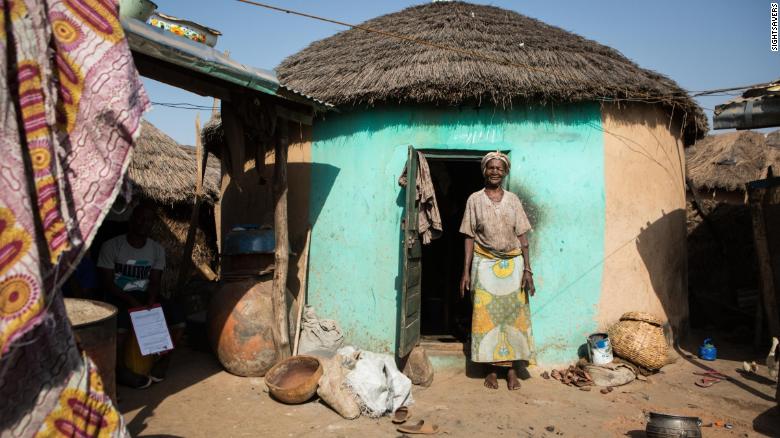

|

| Zeinab Abukari in her home in Yendi district, Ghana. She was infected with trachoma many years ago |

In rural areas the common mode of transmission is flies creeping over children's faces eating the discharge from running eyes and noses. Those flies flit about on human feces to lay their eggs, contaminating the children with fecal matter. The first infections occur at the toddler stage; it takes decades for permanent eye damage to set in, after age 30.

A four-pronged strategy is recommended to break the chain of communication; surgery for advanced cases; annual antibiotic doses in hard-hit areas for the residents; teaching mothers to clean their children's faces frequently; and lastly, the use of pit latrines to reduce the fly populations. Suspicion in poor countries leads to problems in implementing the strategy, however.

About 20 percent of all patients requiring eyelid surgery in Tanzania refuse intervention because rumour has it that a six month recovery period follows surgery and they fear being unable to work to earn their daily bread. Attempts to reassure the reluctant patients so that the procedure can proceed to cure their problem are required, to emphasize that bandages are in place for only 24 hours.

And finally, Nepalis -- as elsewhere in poor countries of the world where custom and habit and lack of alternatives lead to outdoor field evacuation -- have resigned themselves to the use of outhouses rather than continue with the familiar traditions of defecating in fields. Many people were resistant to their use simply out of loyalty to old habits.

|

| A farmer receives an examination for trachoma at a medical center in Vietnam, one of many countries aiming to eliminate the disease. |

Labels: Asia, Bioscience, Disease, Health, Hygiene, Medicine, Poverty

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home