|

| HOW TO QUEST FOR THE HART IN WOODS |

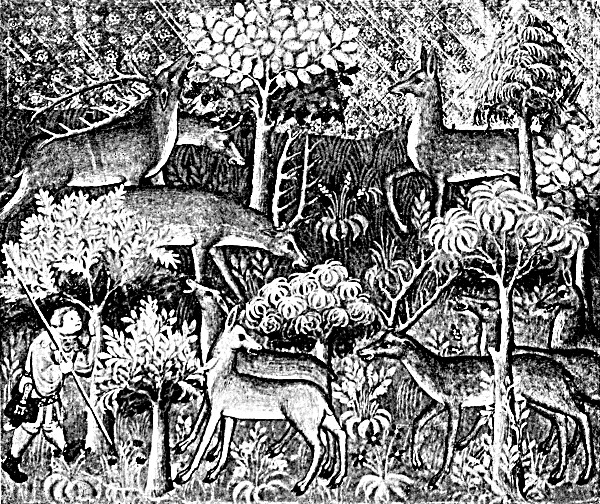

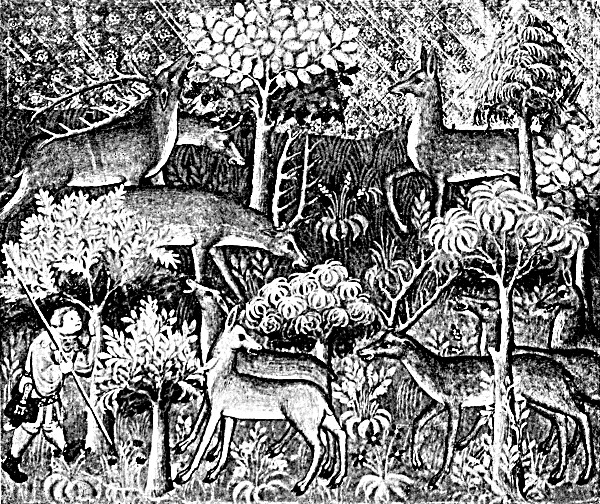

"Cervine and elaphine metaphors abound in medieval art — where stags’ cruciform antlers symbolize Jesus Christ, and illustrated hare and deer hunts

in Haggadot refer, in part, to anti-Semitism — and in the Bible, where

deer (Naphtali’s tribal symbol) take on sexual (Song of Songs),

spiritual (Psalms and Proverbs), and messianic (Isaiah) implications.

Speaking last month at the Chicago Humanities Festival, Paul Reitter, a

German professor from Ohio State, asserted that Bambi’s hunters were at

least partial stand-ins for anti-Semitic persecution in Salten’s 1923

book, “Bambi. Eine Lebensgeschichte aus dem Walde."

Menachem Wecher, The Forward, December 2, 2013

What a peculiar juxtaposition; the modern era's most popular child fantasy film that inspired both fear and hope in child audiences toward whom the Walt Disney film 'Bambi' was directed, came at the very time that Europe's Jews faced the most notoriously existential scheme in modern history for gross annihilation. The anthropological portrayal of hunted wild animals in their forest haven as opposed to the continent-wide strategic search for the presence of Jews to be gathered up, placed in death camps and murdered to satisfy the anti-Semitic death-lust of Nazi Germany.

A wildly popular story of a family of deer and their neighbours, some of whom survived, some of whom did not, as a look at the dark and sinister world of survival of creatures in the wild, threatened by other species' predator instincts, by natural phenomena, and by human hunters. Oddly enough, written by a man who was himself a hunter, but expressed a distaste for those who hunted illegally as poachers. A man who was a citizen of Austria and who hid his Jewishness because of the persecution he suffered as a schoolboy by anti-Jew teachers and other pupils.

The novel, published in German in 1923, is being increasingly identified as an allegory for the persecution of Jews during the early years of the 20th century. Its author was Felix Salten, the title of the book, Bambi: A Life in the Woods. And the content of the book is quite dissimilar in form and content than the later film version the world knows as Disney's 'Bambi'.

When the book was first translated into English in 1928, one American reviewer compared its dark aspect as "profoundly pertinent to the modern experience as The Magic Mountain (1924 Thomas Mann novel]". Felix Salten was born Siegmund Salzmann in 1869 Hungary and when he was four weeks old his family moved to Vienna where his school bullying as a victim of anti-Semitism coloured his outlook on life, and convinced him to hide his Jewishness.

He eventually changed his name to remove its identification of himself as a Jew; in his words he "unmarked" himself. A move he later regretted and reversed, when he became a Zionist under the influence of Theodore Herzl with whom he struck up a close friendship. His family history included a long line of rabbis, but Salten preferred while he was making a name for himself as a novelist, to be secular, to integrate himself in the larger Austrian society.

A propaganda campaign blaming Jewish subversion for the defeat suffered by Germany and Austria during the First World War, inspired the writer to commit to writing his Bambi novel. He was by then a Zionist and travelled to Palestine after which he wrote a travel book with Zionist overtones titled New People on Ancient Soil: A Tour to Palestine.

In Salten's Bambi, he wrote: "The terrible hardship (a harsh winter season and food scarcity) destroyed all their memories of the past, undermined their conscience, ruined all their good customs and manners, and demolished their faith in one another." An understated metaphor transcribing the situation that Jews found themselves in through the diaspora born of their Judean exile; hounded, despised and persecuted. Civilized veneer easily scrubbed away in the face of adverse events.

There are philosophical discussions in Bambi where elderly deer say they will never forgive their persecutors: "He's (humanity) murdered us ever since we can remember ... And now we're going to make friends with him! What stupidity!" Bambi's father speaking of hunting dogs at the bidding of their human masters: "The worst part of it all is that ... they spend their lives in fear. They hate (humans) and themselves ... They kill themselves for (their) sake."

Bambi's father and mother teach their son to trust no one but his own judgement. To ensure that he is always prepared to defend himself. And to do that he must learn to value a solitary life. Salten was forced in his old age to leave Vienna for exile in Switzerland when Hitler annexed Austria. He died in Switzerland in 1945, presumably in the knowledge that the worst oppressor/persecutor and mass murderer of Jews had committed suicide before he himself died.

Before he died Salten addressed the failure of Jewish attempts at integration into the societies they lived within, that those efforts all too often came to nothing, as suspicion and persecution and viral anti-Semitism took on waves of renewal. It might have buoyed his dark view of the sinister world order that seemed to always reject a Jewish presence, had he lived to 1948 to witness a return of the wandering Jew to their Judean heritage in the State of Israel.

Labels: Allegory, Bambi, Bambi: A Life in the Woods, Felix Salten

:focal(1500x943:1501x944)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/57/f7/57f7ba4b-39fb-4cf9-94ab-ab4666ef9055/gettyimages-463214374.jpg)