Inheriting Markers of Trauma

"These are, in fact, extraordinary claims, and they are being advanced on less than ordinary evidence."

"This is a malady in modern science: the more extraordinary and sensational and apparently revolutionary the claim, the lower the bar for the evidence on which it is based, when the opposite should be true."

Kevin Mitchell, associate professor, genetics and neurology, Trinity College, Dublin

"The effects we've found have been small but remarkably consistent, and significant."

"This is the way science works. It's imperfect at first and gets stronger the more research you do."

Moshe Szyf, professor of pharmacology, McGill University, Montreal

"These are clear, consistent findings."

"The field has advanced dramatically in just the past five years."

Tracy Bale, professor, pharmacology, psychiatry, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Director, Center for Epigenetic Research in Child Health and Brain Development

"It’s either the stress of war or the malnutrition of war or both."

"The stress on the system moves the machinery to put down or not put down epigenetic markers."

Randy L. Jirtle, epigenetics researcher. North Carolina State University

|

| The team’s work is the clearest sign yet that life experience can affect the genes of subsequent generations. Photograph: Mopic/Alamy |

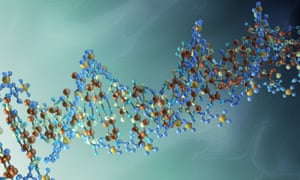

The gene won't be damaged leaving a mutation, but alters the mechanics where the gene becomes converted into functioning expressions.

A decade earlier, scientists reported that children exposed in the womb to the Dutch Hunger Winter -- representing a time of famine toward the end of World War II -- carried a distinguishing chemical mark, or epigenetic signature, on one of their genes. That finding was later linked to differences in health in later life of those children; among distinguishing markers, higher than-average body mass. This new field of study has generated additional studies including those of Holocaust survivors' children.

Studies of the descendants of Holocaust survivors post hints at the heritability of trauma through generations where it is suggested by the studies that some trace of parents' and grandparents' experience with an emphasis on suffering, modifies the following generations' health and that, in turn of the generations that follow; from grandparents to parents to children. Rachel Yehuda of Mount Sinai Hospital and colleagues concluded in 2016 that Holocaust survivors and their children had evidence of methylation on a region of a gene associated with stress, suggesting that the survivors’ trauma was passed onto their offspring.

|

| Children in the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp. Photograph: Imagno/Getty Images |

There are tantalizing hints of the heritability of trauma where studies appear to suggest that some trace of our parents' and grandparents' experience is inherited, and most particularly their suffering in turn modifying the health of descendants, and continuing on to affect their descendants' children. Not all researchers are convinced, however; critics among them contend that biological alterations such studies imply are quite simply implausible. On the other hand, epigenetics researchers insist the solid evidence is more than convincing.

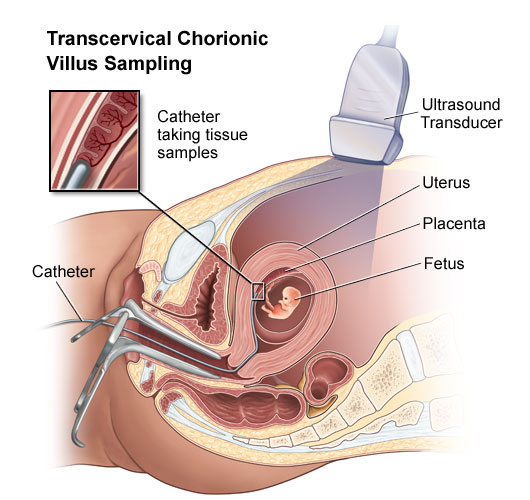

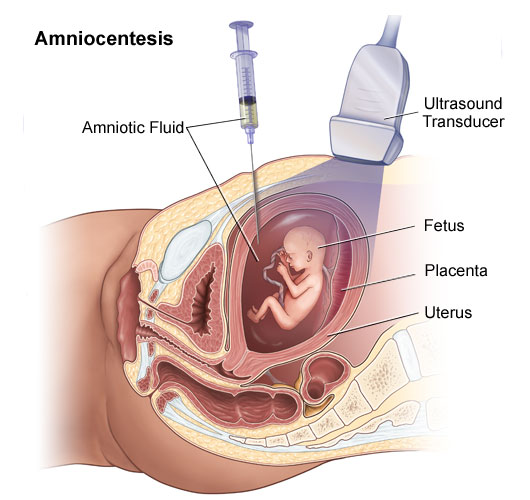

Studies of mice have been cited in support of evidence of trauma-transmission in this debate revolving around genetics and biology. Unlike direct effects, as when a pregnant woman heavily imbibes in alcohol causing fetal alcohol syndrome, the issue is one of stress wearing on a pregnant mother's body, being shared to an extent with her fetus; interfering directly with the normal developmental stages in utero.

The trouble is that no researchers are as yet able to explicate precisely how brain cell changes caused by abuse might be communicated to sperm or egg cells prior to conception.

Following conception, when sperm meets egg the process of cleansing or 'rebooting' occurs when most chemical marks on the genes are stripped away. As the fertilized egg grows and develops, genetic reshuffling takes place with cells specializing into various components of functionality such as brain cells, skin cells and so on. The big question: How is it possible that a signature trauma might survive all these processes?

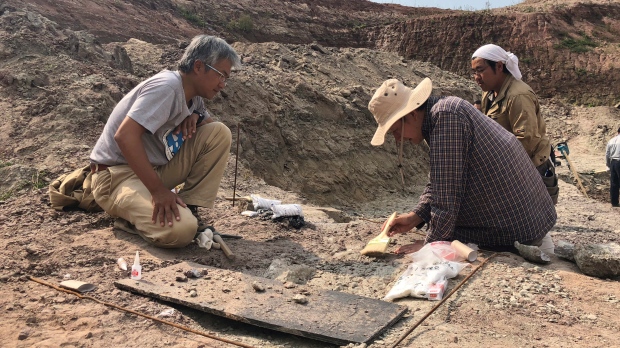

Scientists at the University of Maryland School of Medicine have raised male mice in difficult environments, such as periodically tilting cages or leaving lights on throughout the night hours which effects alter subsequent behaviour of the affected mice's genes, known to alter how the mice manage surges of stress hormones. It is that change, associated with alterations in the manner in which their offspring handle stress that is notable.

According to Dr. Bale who led that research, young mice become less reactive with their hormones in comparison to the behaviours of control animals. The generational changes are not inevitable, however; nutritional intervention can alter the course of those behavioural changes. For example, should the father be possessed of generational markers and the mother the benefit of good nutrition the child born to them can be free of such markers.

"By no means is it saying that whenever there’s trauma, that means it’s going to be transmitted."

"The epigenetic story is optimistic because it allows for the possibility of reversibility through maternal nutrition."

Professor Dora Costa, lead author, Civil War study, economist, UCLA

|

/arc-anglerfish-tgam-prod-tgam.s3.amazonaws.com/public/WXXHGT22WRDVLOZX6KPO67EYGA.jpg)

/arc-anglerfish-tgam-prod-tgam.s3.amazonaws.com/public/JQTR2HVMPJDQZDLCMU7V2TJODU.jpg)

/arc-anglerfish-tgam-prod-tgam.s3.amazonaws.com/public/BQEDUDV73JDCHMROYUFG6FEPRE.jpg)

/arc-anglerfish-tgam-prod-tgam.s3.amazonaws.com/public/T3ENIVGE25D5NOKM3Q5TMVDBG4.gif)

/arc-anglerfish-tgam-prod-tgam.s3.amazonaws.com/public/GQNIQDFXAZDTHKEQTLNTBLCDLY.jpg)

/arc-anglerfish-tgam-prod-tgam.s3.amazonaws.com/public/UKLQWL2RWFAGFNH7GQ4LILHGUU.jpg)

/arc-anglerfish-tgam-prod-tgam.s3.amazonaws.com/public/XWXJ2J3YWVANJNZO6GELKPBSQU.jpg)