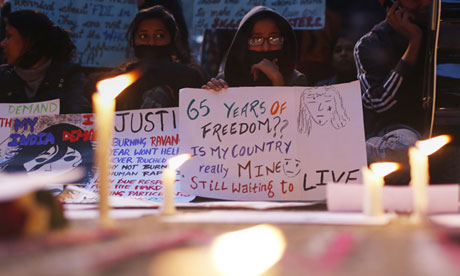

Mahesh Kumar / AP

Indian students shout slogans during

a protest rally in Hyderabad, India, Monday, Dec. 31, 2012. The

gang-rape and killing of a New Delhi student has set off an impassioned

debate about what India needs to do to prevent such a tragedy from

happening again. The country remained in mourning Monday, two days after

the 23-year-old physiotherapy student died from her internal wounds in a

Singapore hospital.

The Indian woman who was brutally

gang raped and later died of her injuries was cremated Sunday, as her

friends revealed she was engaged to marry the man attacked alongside

her.

The pair were to be married in February,

The Telegraph reported.

“They had made all the wedding preparations and had planned a wedding

party in Delhi,” said Meena Rai, a friend and neighbour told the

newspaper. “I really loved this girl. She was the brightest of all.”

India remained in mourning Monday, two days after the 23-year-old

physiotherapy student died from her internal wounds in the Singapore

hospital where she had been sent for emergency treatment. Six men have

been arrested and charged with murder in the Dec. 16 attack on a New

Delhi bus. They face the death penalty if convicted, police said.

Sajjad Hussain / AFP / Getty ImagesIndian

protesters light candles around a mannequin representing the rape

victim during a rally in New Delhi on December 31, 2012. The family of

an Indian gang-rape victim said they would not rest until her killers

are hanged as they spoke of their own pain and trauma over a crime that

has united the country in grief.

The country’s army and navy also cancelled New Year’s celebrations

out of respect for the woman, whose gang-rape and murder has set off an

impassioned debate about what the nation needs to do to prevent such a

tragedy from happening again.

Protesters and politicians have called for tougher rape laws, major

police reforms and a transformation in the way the country treats its

women.

“To change a society as conservative, traditional and patriarchal as

ours, we will have a long haul,” said Ranjana Kumari, director of the

Center for Social Research. “It will take some time, but certainly there

is a beginning.”

“She has become the daughter of the entire nation,” said Sushma Swaraj, a leader of the opposition Bharatiya Janata Party.

Hundreds of mourners continued their daily protests near Parliament demanding swift government action.

“So much needs to be done to end the oppression of women,” said

Murarinath Kushwaha, a man whose two friends were on a hunger strike to

draw attention to the issue.

Manish Swarup / AP Indian

members of All India Students' Association (AISA) shout slogans during a

protest in New Delhi, India, Monday, Dec. 31, 2012. The gang-rape and

killing of a New Delhi student has set off an impassioned debate about

what India needs to do to prevent such a tragedy from happening again.

The country remained in mourning Monday, two days after the 23-year-old

physiotherapy student died from her internal wounds in a Singapore

hospital.

Some commentators compared the rape victim, whose name has not been

released by police, to Mohamed Bouazizi, the Tunisian street vendor

whose self-immolation set off the Arab Spring. There was hope her

tragedy could mark a turning point for gender rights in a country where

women often refuse to leave their homes at night out of fear and where

sex-selective abortions and even female infanticide have wildly skewed

the gender ratio.

“It cannot be business as usual anymore,” the Hindustan Times newspaper wrote in an editorial.

Politicians from across the spectrum called for a special session of

Parliament to pass new laws to increase punishments for rapists —

including possible chemical castration — and to set up fast-track courts

to deal with rape cases within 90 days.

The government has proposed creating a public database of convicted

rapists to shame them, and Prime Minister Manmohan Singh has set up two

committees to look into what lapses led to the rape and to propose

changes in the law.

The Delhi government on Monday inaugurated a new helpline — 181 — for women, though it wasn’t working because of glitches.

Responding to complaints that police refuse to file cases of abuse or

harassment brought by women, the city force has appointed an officer to

meet with women’s groups monthly and crack down on the problem, New

Delhi Lt. Gov. Tejendra Khanna said.

“We have mandated that any time any lady visits a police station with a complaint, it has to be recorded on the spot,” he said.

Kumari said the Delhi police commissioner sent her a message Monday

asking her group to restart police sensitivity training that it had

suspended due to lack of funds.

There have also been proposals to install a quota to ensure one-third of Delhi’s police are women.

There also have been signs of a change in the public debate about crimes against women.

Other rapes suddenly have become front-page news in Indian

newspapers, and politicians are being heavily criticized for any remarks

considered misogynistic or unsympathetic to women.

A state legislator from Rajasthan was ridiculed Monday across TV news

channels after suggesting that one way to stop rapes would be to change

girls’ school uniforms to pants instead of skirts.

“How can he tell us to change our clothes?” said Gureet Kaur, a

student protester in the Rajasthani town of Alwar. “Why can’t girls live

freely?”

Some activists have accused politicians of being so cossetted in

their security bubbles that they have no idea of the daily travails

people are suffering.

Kumari said the country was failing in its basic responsibility to

protect its citizens. But she was heartened to see so many young men at

the protests along with women.

“I have never heard so many people who felt so deep down hurt,” she said. “It will definitely have some impact.”

With files from National Post staff