The Ethics and Practicalities of Preemie Survival

"They told me every absolute horror story in the book. They told me that he wouldn't survive, and if he did by some miracle survive, he would have no quality of life ... and most likely be a burden on me."

"He lights up my whole entire life. It's incredible."

"I am so happy. I am so proud of him and everything he has done."

Jennifer Lake, London, Ontario

|

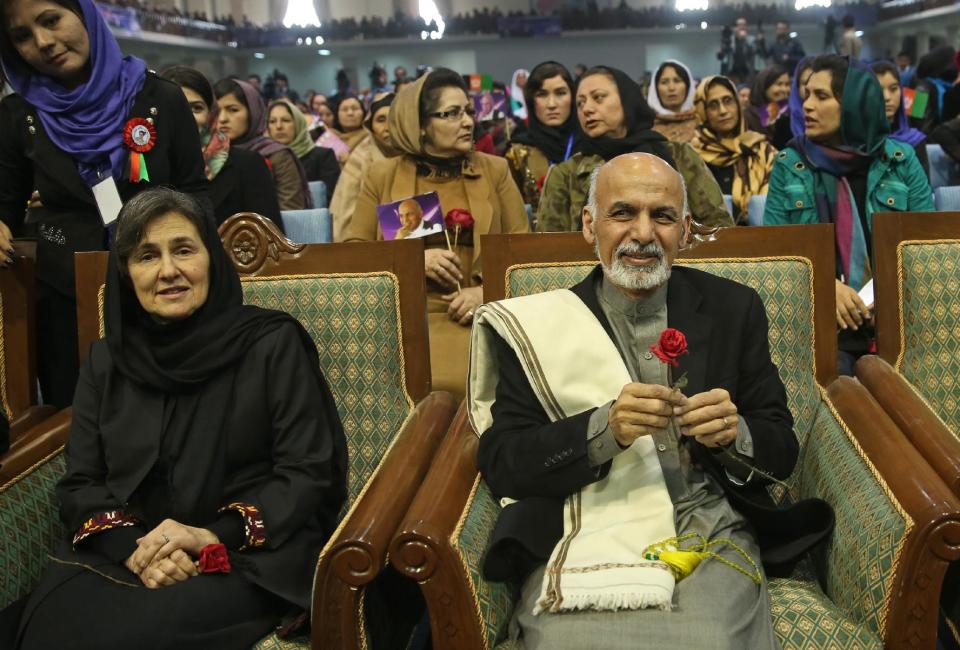

| Today, despite some disabilities, Carter Lake is a happy six-year-old preparing to enter Grade 1. Tyler Anderson / National Post |

"We have to get our hands dirty, and not just lie to people to keep it simple."As in most areas of medical treatment and bioscience there is never full agreement. There will always be some opinions based on personal experience, study and perception of any issue where disagreement relating to therapies and outcomes, purpose and practicality intersect whose result is a minefield of doubt for those affected, having to make decisions based on winnowing out what appears most reasonable to their untutored minds, given the advice they are exposed to.

"Doctors don't actually say, 'We don't think it's worth ...' They say, 'it doesn't work', and 'That's a lie. It's not true ...' When you realize you have been lied to by doctors, it's extremely hurtful."

Dr. Annie Janvier, neonatologist, St.Justine Hospital, Montreal

"You can imagine a family caring for a severely handicapped child, they certainly cannot express in a negative way the fact they have to care for their child. But there is still a struggle, there are consequences on brothers and sisters, on the parents themselves."

Dr. Thierry Lacaze, neonatologist, Children's Hospital of Eastern Ontario

"It's a kind of red flag. Maybe we shouldn't go here, maybe this is pushing our scientific, technical abilities beyond a point where they are of benefit to families and society and, most of all, the tiny babies."

"Some of the time I had to struggle to suppress the thought 'How unlucky for these families that their child was born with access to an NICU [neonatal intensive care unit]. Wouldn't they have been more fortunate if they had been living in a remote area ... where the baby would have died instead of being put through days and weeks of intensive, high-tech medicine, with virtually no chance of surviving, or surviving without overwhelming impairments."

Arthur Schafer, head, Centre for Professional & Applied Ethics, University of Manitoba

And what could be more polarizing than making life-and-death decisions based in conflicting advice, frightening and intimidating, whose outcome in retrospect may have been directed toward what would later be considered to be a wrong decision leading to anguish and misery?

|

| Carter Lake in London's St. Joseph's Hospital after being born at just 22 weeks' gestation. Doctors had said they wouldn't keep him alive if delivered before 24 weeks, but he ended up in the ICU after being born unexpectedly at home and rushed to hospital. Handout |

When Jennifer Lake spontaneously gave birth to a 22-week-old baby at home, she knew beforehand that doctors would allow the baby to die if it was delivered under 24 weeks' gestation. Doctors had informed her that resuscitation and life support were considered futile. But her baby was rushed to hospital by ambulance and staff there absorbed him into the intensive care unit. Even though doctors and nurses at St. Joseph's Hospital in London, Ontario recommended he be taken off life support.

At the conference this past week of the Canadian Bioethics Society, attendees heard from a variety of people with various views on the Canadian Paediatric Society's recommendation that babies born at 22 weeks or less be allowed to die naturally. Some doctors and ethicists feel that individual babies' gestational ages differ so that the cut-off at 22 weeks represents an arbitrary threshold, where flexibility and open communication might serve a better purpose.

Dr. Thierry Lacaze, head of the Canadian Bioethics Society fetus and newborn committee agreed that basing life-and-death determinations on the standard convention of gestational age is imperfect. He made a vow that the guideline is in line for an alteration post-consultation among health-care professionals and the parents of these vulnerable preemies. But he spoke also of small local hospitals whose doctors haven't the expertise to make such decisions even though they are exposed to care for 20 to 30 percent of preemies.

Still, insists Arthur Schafer from his academic perch, reliance on the tradition of gestational age in judging the viability of a preemie provides a yardstick for those without experience to rely upon, as they grapple with these decisions affecting parents of babies who may if they survive have multiple quality-of-life-affected physical abnormalities. Often such decisions whether or not to allow a struggling baby to live or die must be made in the delivery room.

Babies born partway through normal gestation are unable to live for much longer than a few hours on their own. Their lungs are not fully formed so they must be dependent on an artificial breathing machine and they require tube feeding as they are incapable of feeding normally. They face a high risk of disabilities such as blindness and deafness, and cerebral palsy and cognitive impairment. The Canadian Paediatric Society recommends palliative care "since survival is uncommon".

For neonatal births of 23 to 25 weeks counselling and discussion with parents relating to decisions on intensive care is suggested. But what might seem to be standard policy is not actually that, differing from region to region, hospital to hospital. And to make for even more confusion, a new American study published in the New England Journal of Medicine found that 23 percent of 22-week-babies survived under active treatment, and nine percent survived with little impairment.

By the time very premature babies have reached their teenage and adult years most personally consider their quality of life, despite any disabilities, to be equal to that of others without their birth background, according to research findings by McMaster University neonatologist Saroj Saigal. As for Carter Lake, now six and prepared to enter grade one, he is intelligent, speaks well and is a happy boy, despite that he relies on a wheelchair and suffers from vision problems in one eye.

|

Tyler Anderson / National Post Jennifer Lake and her six-year-old son Carter pose for a portrait at their home in London, Ontario, Thursday May 28, 2015.

|

Labels: Canada, Family, Health, Social Welfare