CRISPR Foods, Everyone?

"This is not Frankenfood."

"There is nothing taken out or added to the plant. It's what nature would have produced."

"[Edits in crop plants] alter the mix of fatty acids to produce soybeans to make, for example, an improved cooking oil]. Better than olive oil."

Dr. Andre Choulika, chief executive, Cellectis

|

| Popsci.com files -- CRISPR illustration |

"We've never been against any of this technology. We don't say it's inherently bad or these crops are inherently dangerous."

"It's just [that] they raise safety issues, and there should be required safety assessments."

Michael K. Hansen, senior staff scientist, Consumers Union

"The objection that people have is a more visceral and vague objection to messing with DNA."

"It's hard to see that the public would see the difference [in this alternate type of gene-editing, as opposed to genetically modified]."

Richard C. Mulligan, professor of genetics, Harvard Medical School

|

| Photo: Stefan Janssen -- The first CRISPR meal, featuring genetically altered cabbage |

Soon to appear on supermarket shelves everywhere is a new generation of crops identified as gene-edited, not genetically modified. New precision instruments capable of snipping and tweaking DNA at exact places on a plant's cells. And the new process of editing is capable of producing non-browning mushrooms, or longer-lasting potatoes, or soybeans where the fatty acids are 'healthier'.

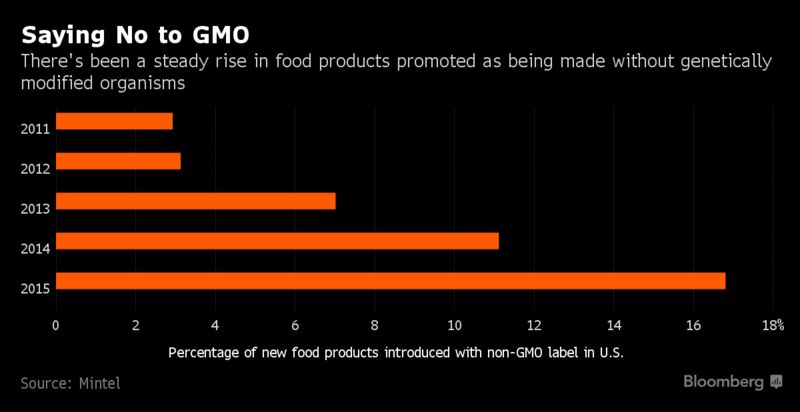

The older methods so discredited in the consuming public's mind of engineered genes, not permitted entry to some countries and certainly not into the European Union, the newer techniques such as CRISPR do not add genes from other organisms into the host plants. Gene-edited crops are already being raised in several U.S. states, not requiring oversight or regulations; some have even been eaten, unbeknownst to the consumer.

Cellectis, one company that is developing gene-edited crops, introduced the world to them when it hosted a dinner at an upscale restaurant, inviting scientists, journalists and celebrities to attend and eat dishes produced from gene-edited soybeans and potatoes. The potatoes were edited to remain fresher and not result in the production of carcinogens when fried.

A subsidiary of Cellectis, Calyxt is in the developmental stages of a new version of wheat crops, including one enhanced to greater fungal diseases resistance. And yet another wheat crop that will be less carbohydrate-intensive, and higher in dietary fibers. DuPont Pioneer is another company developing gene-edited crops, using the technology for a new type of corn -- not for consumption, but for producing starch, to be used in adhesives.

Regulations as they currently exist were originally written with the earlier generation of genetically modified organisms in mind. That technology saw scientists using bacteria and viruses -- usually from plant pests -- to insert new genes into the nuclei of plant cells to merge with the plant's DNA. While it was a successful merging, it was realized that there was no way to control where the new genes would be inserted, leading to concerns of possible genetic disruptions or crossbreeding occurring with non-GMO crops.

A comparison has been made, to help people better understand the new process . . . to moving a cursor in a word processor to a specific location to insert a small text alteration . . . and this is the way that edited food crops work. The European Commission has mounted a scientific panel, as part of the ongoing debate over this new technique, commissioning it to study gene-editing.

Calyxt uses a technique named Talen in its gene-editing, to create molecules to act as a template matching a specific area of DNA, and making an incision at that point. For the soybeans using the Calyxt method, turning off two genes was the only alteration required.

Labels: Agriculture, Biochemistry, Bioscience, Genetic Modification

![[beta amyloid plaques]](http://cdn1.medicalnewstoday.com/content/images/articles/315/315488/beta-amyloid-plaques.jpg)

![UNDATED - VANCOUVER, BC - Submitted January 12, 2011 - Dr. Weihong Song, for use in Alzheimer's story. (For story by Gerry Bellett.) (Photo courtesy Martin Dee, UBC) Handout [PNG Merlin Archive]](http://wpmedia.vancouversun.com/2017/01/undated-vancouver-bc-submitted-january-12-2011-dr1.jpeg?quality=55&strip=all&w=840&h=630&crop=1)